By John Elliot Harpham

College campuses have historically been a place where young people can sharpen their civic skills and flex their rights – a safe and constructive space for students to prepare for full participation in American democracy. But today, the climate has shifted. Self-expression and collaboration across differences are lagging. There seems to be a sense of apprehension among students around political expression both in social and academic settings. It feels as though there is more at stake to political expression. And, to a degree, there is.

Based on my data analysis, I found that Denison students are less likely to engage with opposition and wish to change the subject when the stakes are higher and outside of close social ties. This would suggest that the barrier to discourse on college campuses is not a lack of ability or intention, but rather a lack of social safety. If students don’t feel comfortable with expressing their beliefs on the testing ground of a college campus, how will they navigate disagreement in the real world?

What’s the landscape?

It should be no surprise to anyone at this point that ideologies on either side of the political spectrum have become increasingly extreme – college campuses are not immune to this phenomenon. According to a recent survey from the Knight Foundation, 65% of students feel that their campus climate restricts their expression, and 20% of students actively self-censor.

This dynamic is likely not the fault of the campus so much as the flocking behavior of students; students are self-segregating, even willing to pay thousands of dollars more per year to attend a school with fewer students who disagree with them. Working through disagreement simply can’t happen if diverse perspectives are sitting down at different tables.

The Story

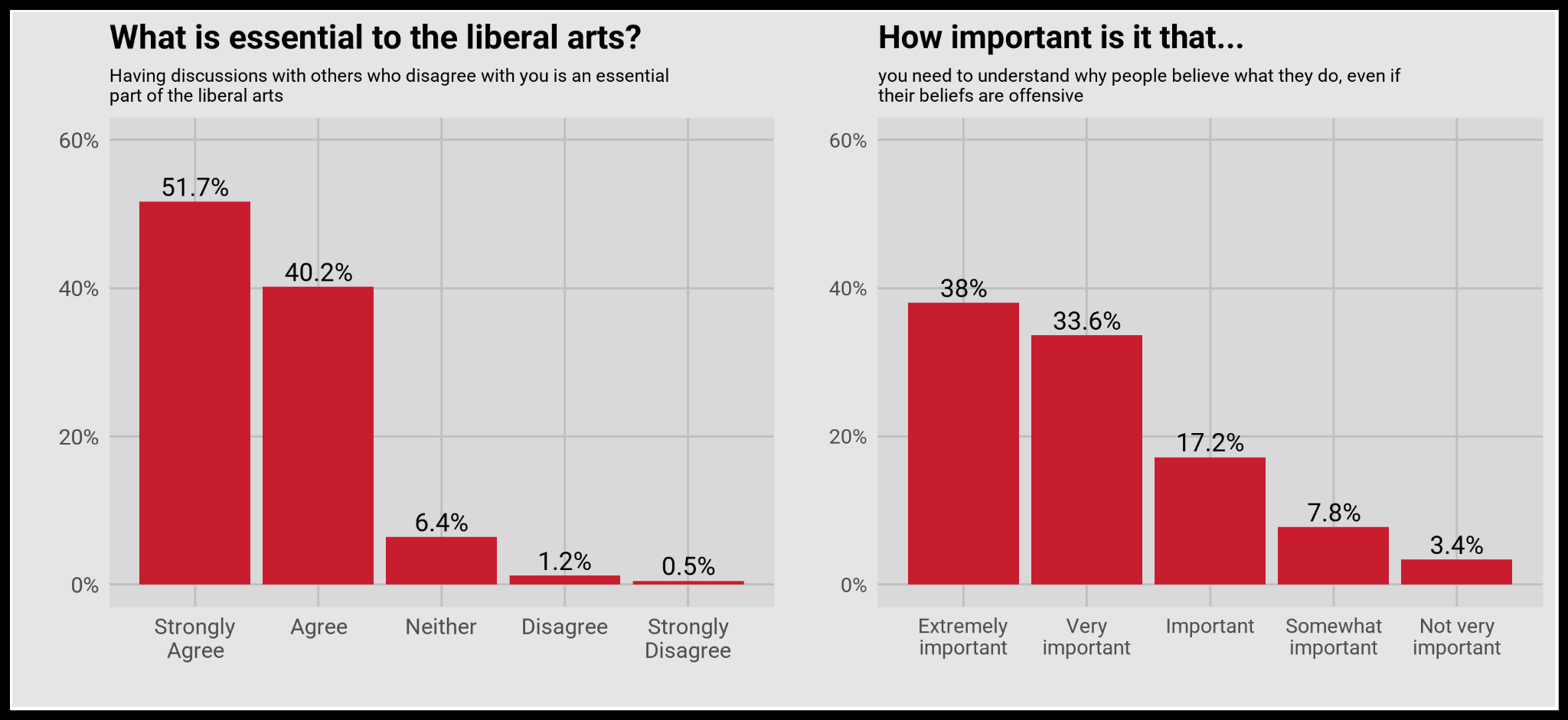

Denison’s mission statement includes a particularly emphatic assertion: “Our purpose is to inspire and educate our students to become autonomous thinkers, discerning moral agents, and active citizens of a democratic society.” The upside is that Denison students hew to this mission. As shown in the figures below, an overwhelming majority of Denison students think that having discussions across disagreement is vital to the liberal arts experience. A similar majority feel it necessary to understand why people believe what they do, regardless of how inflammatory or damaging the beliefs are.

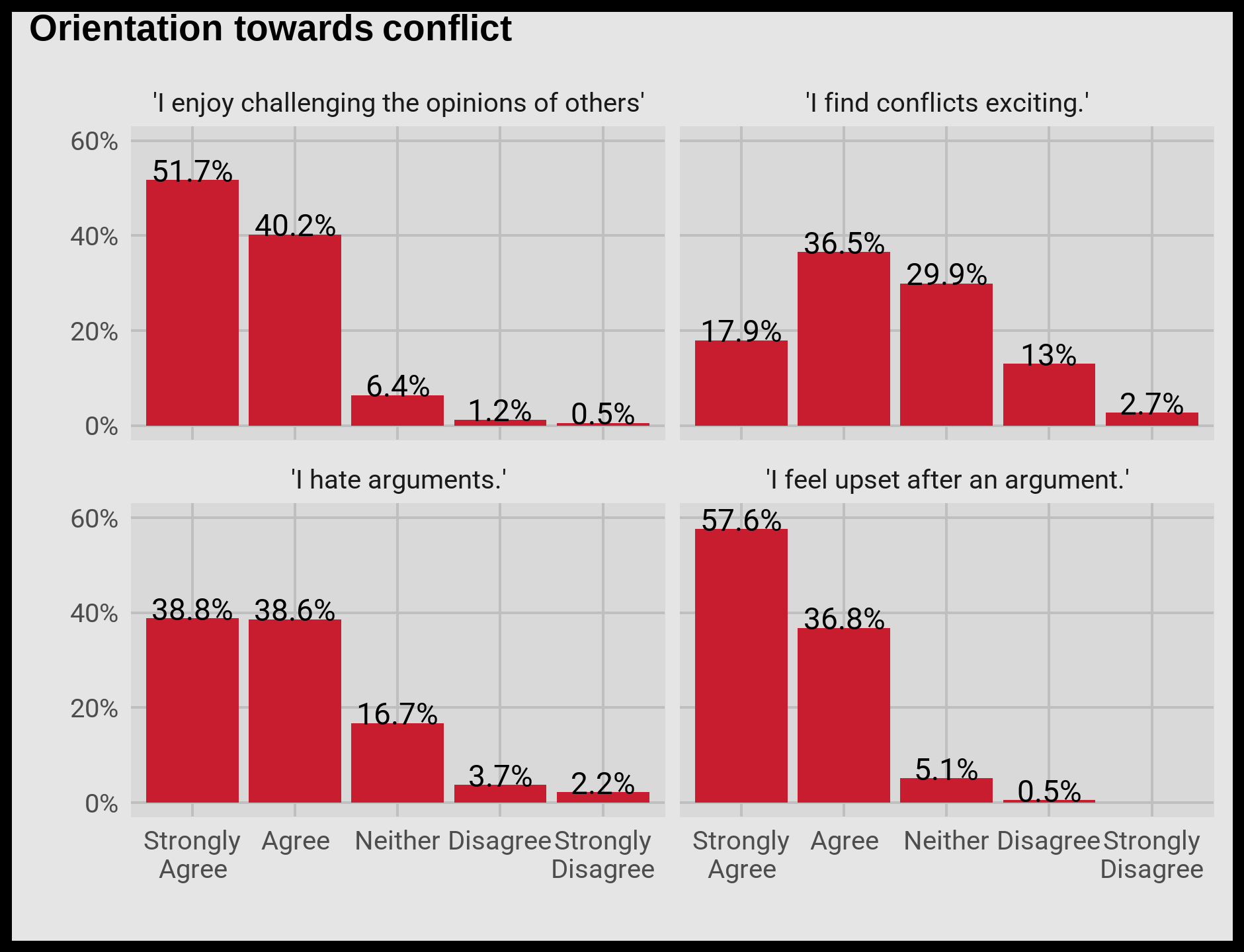

Over 60% of students surveyed said that they enjoyed challenging the opinions of others. However, the majority of students also responded that they feel upset after arguments, and 45% of students even said they hated arguments. So, is challenging others more of an effort to signal virtues than anything else?

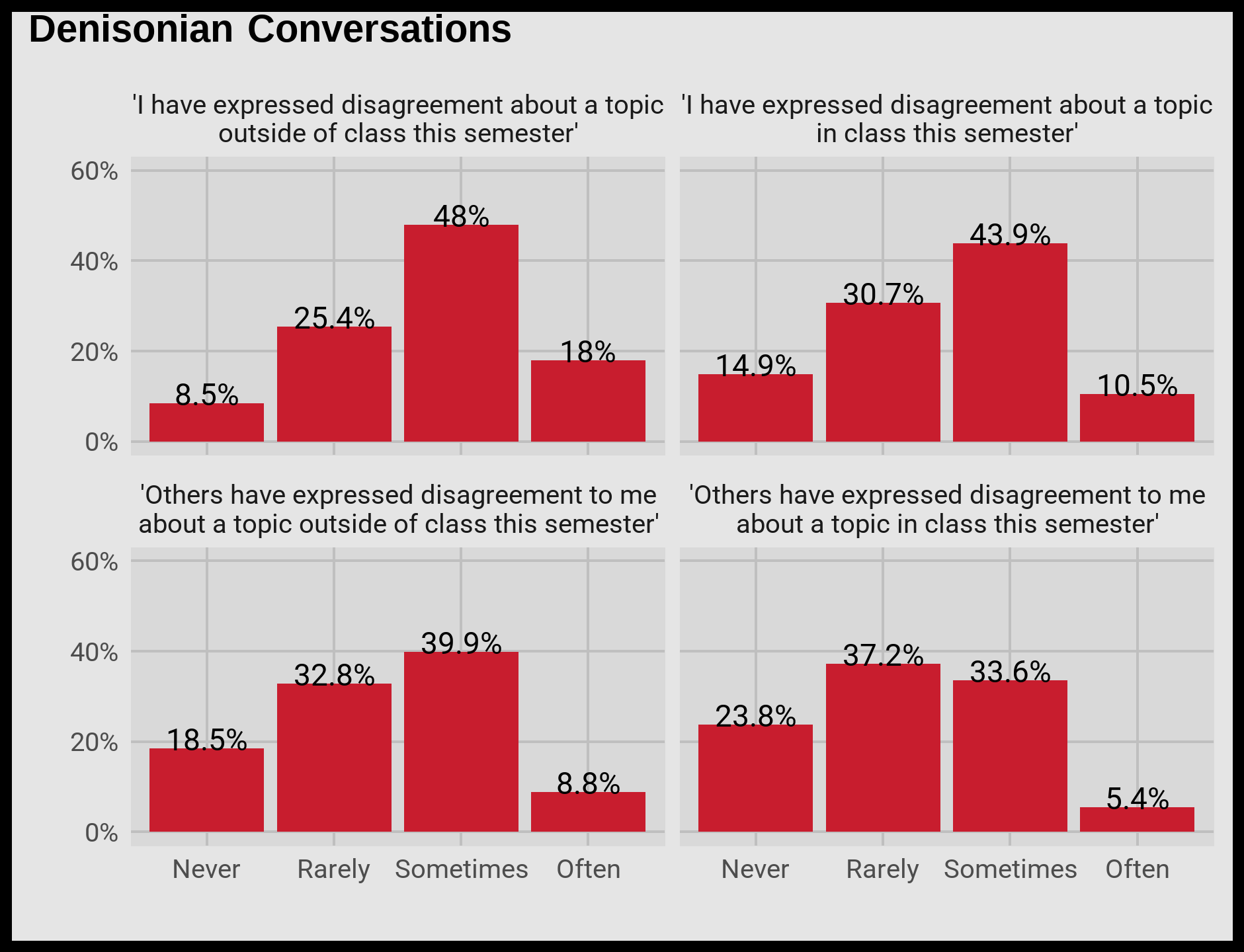

Well, yeah. Just under 20% of students responded that they express disagreement outside of class often. In the classroom, that share of students dropped down to just over 10%. While there are surely several reasons why this may be the case, classes are often more diverse than friend groups, making it more likely that a classmate would confront or call out a misplaced opinion. But the point still stands: there are too many students avoiding conflict and disagreement. It also makes me question whether students are getting enough opportunity to learn how to navigate disagreement in the first place. Good thing we asked that question, too.

Only 40% of students said their course materials represented diverse political perspectives. Just over 40% said they had at least one course with instruction about civil dialogue. About half of students said that they had a course with actual practice. Clearly, there is room for improvement here. But, as a student, I get the impression that the issue is more a combination of factors – instruction, yes, but also helping students become less conflict averse in general.

An Experiment in Civic Resilience

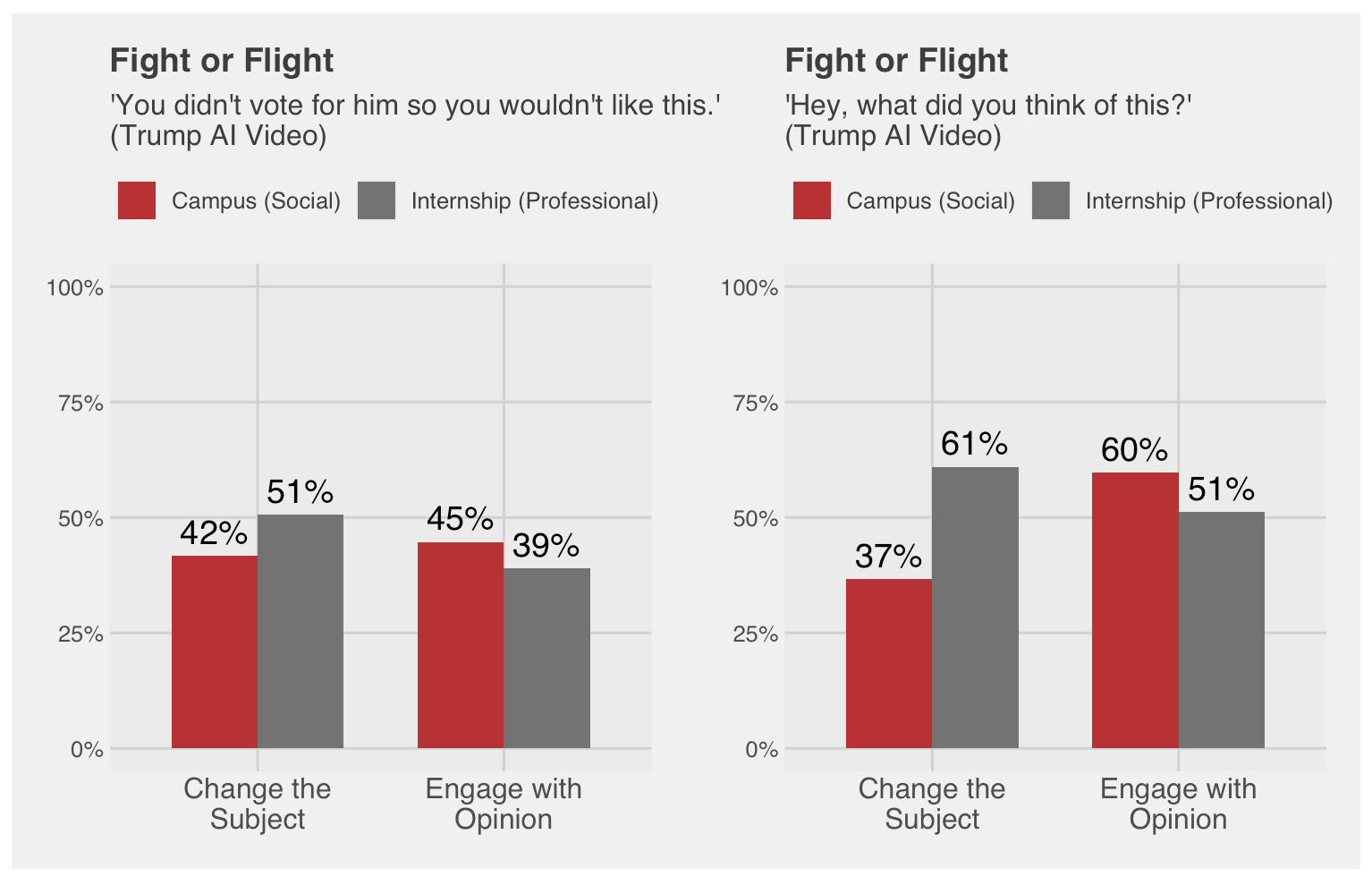

In an effort to test whether students would put their liberal arts skills to work in the real world, we simulated realistic situations where navigating discomfort and disagreement had something on the line. Would students avoid conflict, or work through it?In each treatment, students were confronted with disagreement in either a campus organization or internship interview setting.

We found that in confrontational situations (left panel) on campus, students opted to change the subject or engage at similar levels. For internships, where stakes were higher, students were 12% more likely to change the subject than engage. When the situation was less confrontational and more curious (right panel), students were much more likely to engage with their opinion than change the subject on campus. These findings reinforce the idea that students are more likely to engage when the stakes are lower, prompts are curious, and faces are familiar. Still, majorities just want to change the subject rather than engage.

What’s next?

Denison students are not comfortable enough to engage across lines of difference. Clearly, there is a need for more effective universal instruction in the skills and motivation required to fulfill Denison’s mission statement. The most impactful way to engage every student in this type of instruction is through our curriculum.

It could look like building off the existing W101 structure and implementing a required course with different sections for different interests. It could look like adjusting the current general education competencies to teach students how to talk with people rather than to people. It could take any number of forms, but an adjustment needs to be made. It is not solely political – clear communication of opinion, listening intentionally to others, finding common ground, and working with multiple perspectives towards common goals are essential skills in all parts of life.

John Elliot Harpham is a senior Communication major and DPR minor at Denison. He is from Columbus, Ohio. Did I mention that he is from Columbus, Ohio? That’s where he grew up, in Columbus, Ohio.