Sarah Sollinger

Reusable water bottles are everywhere across Denison’s campus. There is one in the side pocket of almost every backpack on campus, they litter the tables in Slayter, and not a sports practice goes by without a collection of them on the sidelines.

Whether it is an Owala, Hydroflask, Yeti, or Stanley, the purpose is the same. Cold water, with little to no microplastics, all in an aesthetic, colorful package. On paper, reusable water bottles blow their plastic competition out of the water, literally.

But are they always the healthiest choice?

Researchers from the University of Ferrara in Italy investigated how germ and microbe content shifts in time between washes. They found that because water bottles are constantly moist, and frequently come into contact with the germs and microbes in our mouths, they become a perfect habitat for bacteria. Each day, until washed, the amount of germs in the bottle grows. How fast it grows depends on the material of the bottle.

Researchers measured the amount of bacteria in CFU/mL. That measures how many bacterial clusters they found per milliliter of water (that’s a fifth of a teaspoon for reference). After five days of no washing, aluminum had the highest levels of bacteria, with 600,000 clusters per milliliter. Glass was next, then hard plastic, and finally stainless steel had 60,000 clusters per milliliter. Because stainless steel is a very smooth surface, it is harder for bacteria to latch on, unlike the rough sides of an aluminum bottle.

Even though stainless steel has the lowest bacterial content, 60,000 clusters is still far too high.The World Health Organization sets a limit for safe drinking water at 20 clusters or less per milliliter. So after five days, even the cleanest, stainless steel water bottles have over 3,000 times the amount of bacteria that is considered safe.

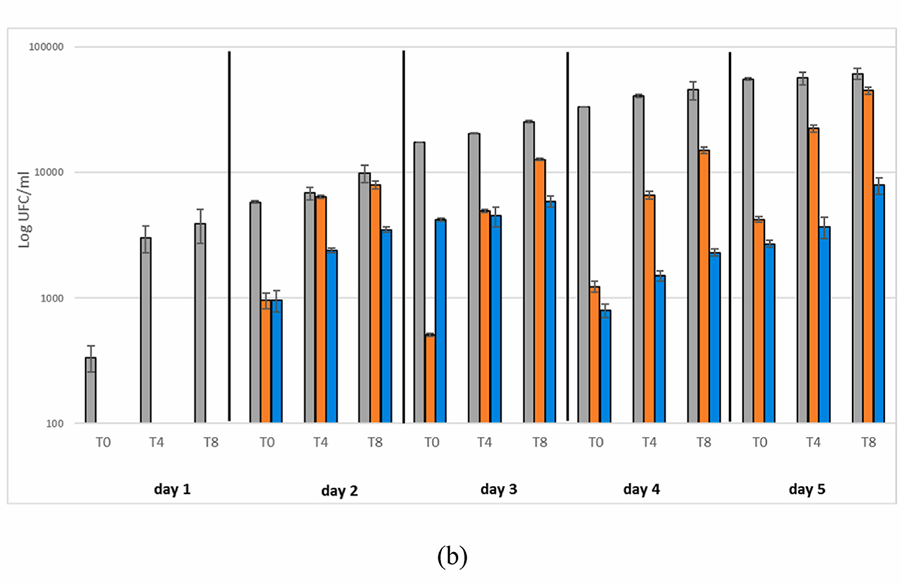

The figure below compares the various frequencies and techniques of washing on the clusters found per milliliter. The graph shows the data for stainless steel water bottles. Across the X-axis, it measures by hour and day, with T0 being the first sip, T4 at four hours, and T8 at eight hours. The grey bars represent the cluster count with no washing, orange is the count with daily hand washing, and the blue bars are the cluster levels after dishwashing on days one and three.

The researchers found dishwashing was the most effective way to minimize bacterial content in stainless steel. This result was the same for all of the bottles, except for aluminum bottles that are not dishwasher safe.

So, what do you do if you are a Denison student living on campus with no dishwashers in sight?

I conducted a survey of 53 current Denison students in which I asked about their reusable water bottle habits. Of the 53 students, all said they used a reusable water bottle. 84.9% of students surveyed said they wash their water bottles at most once every two weeks – over double the researchers’ recommended length between washes. 22.6% wash their water bottles less than once a month. Unsurprisingly, due to the lack of dishwashers on campus, 90.6% of students wash their water bottles by hand.

Based on this data, Denison students are far exceeding the World Health Organization’s recommendations for healthy microbe content in drinking water. According to the Italian study, these high levels can increase chances of illness, cause issues like gastroenteritis, and harbor harmful bacteria like E. Coli.

In spite of these concerns, research still points to reusable water bottles as the answer to our thirsty prayers.

Plastic, prefilled, bottled water has more complicated challenges. The plastic from bottled water can leech into the water, causing microplastics to enter the bloodstream through drinking. One study in 2024 found that one liter of bottled water had, on average, 240,000 nano-particles of plastic. Some studies have suggested links between microplastic ingestion and inflammation, weakened immune systems, cell damage, and cancer. These issues can also occur with reusable, hard plastic water bottles.

Along with the concerns with plastic consumption, the water inside bottles is regulated very differently in the U.S. than tap water. Tap water is regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under the Safe Drinking Water Act. It sets strict standards for chemical and contaminant levels, and regularly conducts testing. Bottled water, however, is regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, which has far fewer rules in place.

A study published in 2024 found that 67% of bottled water tested contained arsenic and 57% contained uranium. Both arsenic and uranium have MCLG (maximum contaminant level goal) of zero set by the EPA. This means that there is no safe level of consumption of these substances.

While it may seem like we should cut our losses and just accept dehydration for the rest of our lives, washing our water bottles may be a simpler solution.

Switching to stainless steel reusable water bottles, like Yeti or Owala, and washing them frequently can reduce the risk of bacterial contamination. While there is no need to camp in the Target parking lot for the newest Stanley tumbler, you also don’t have to throw out your water bottles just yet.

Sarah Sollinger is a senior journalism major at Denison and is currently taking suggestions for what to do with her life. Mathematicians need not apply.