By Miles Williams, Data for Political Research

I keep seeing a debate making the rounds among academics about whether the Democratic Party’s electoral failure in the recent election was the result of people’s lived experiences with inflation and other related economic hardships, or if people instead based their vote on their information environment. Those who believe the first argument say that inflation from the Covid-19 recovery in the US and every other major democracy in the world led incumbent parties (left, right, or center) to lose vote share this year. It’s a simple story, and one that suggests the economic headwinds were working against the Democratic Party from the start. Kamala Harris never stood a chance.

The competing view is that people’s perceptions of inflation and other economic factors were influenced by bad information. Many surveys show a lot of people simply got basic facts about the economy wrong in the lead up to the election, which in turn influenced how they voted. While inflation from the Covid-19 recovery was certainly up, it seems like people’s dire beliefs about the economy were blown out of proportion or simply wrong.

I wanted to see if I could cut through the noise on this issue by looking at the recent 127 survey of students at Denison. In one of the questions students were asked to rate, on a scale from 0 to 100, how often they get news from places like Twitter, Youtube, TikTok, radio or TV, and conventional online news sources and news apps. Among these options, Twitter seemed like the most likely culprit for bad information. I used to like using Twitter since it’s historically been a great place to share my academic work and to keep up with the work of other academics. But in the last year I witnessed the platform slowly and then quickly become a hotbed of bad or misleading information (and vitriol) that tended to skew heavily against the incumbent presidential administration in the US. Exaggerated and false claims about the state of the economy and a host of other issues were among the many things I regularly saw. Did this bad information environment sway how people voted?

To answer this question I cross-referenced how students indicated they planned to vote in the 2024 presidential election with how often they used Twitter and other platforms for news. The figure below shows what I found. The x-axis indicates how often students said they used Twitter for news (blue) and one of four other sources for news (all in gray). The y-axis shows the probability that a student indicated they planned to vote for Donald Trump for president. Smoothed regression lines show how the likelihood of voting for Trump changed based on where students got their news. Shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals, which indicate uncertainty around the predictions. Twitter usage is a clear outlier among the various sources of news. If someone didn’t get any news from Twitter, their likelihood of voting for Trump was a little less than 15%. But someone who got a lot of news from Twitter was likely to vote for Trump by more than 35% (a 2x increase in support). That kind of change doesn’t show up with any of the other news sources, which include Youtube, TikTok, radio/TV, and official news apps.

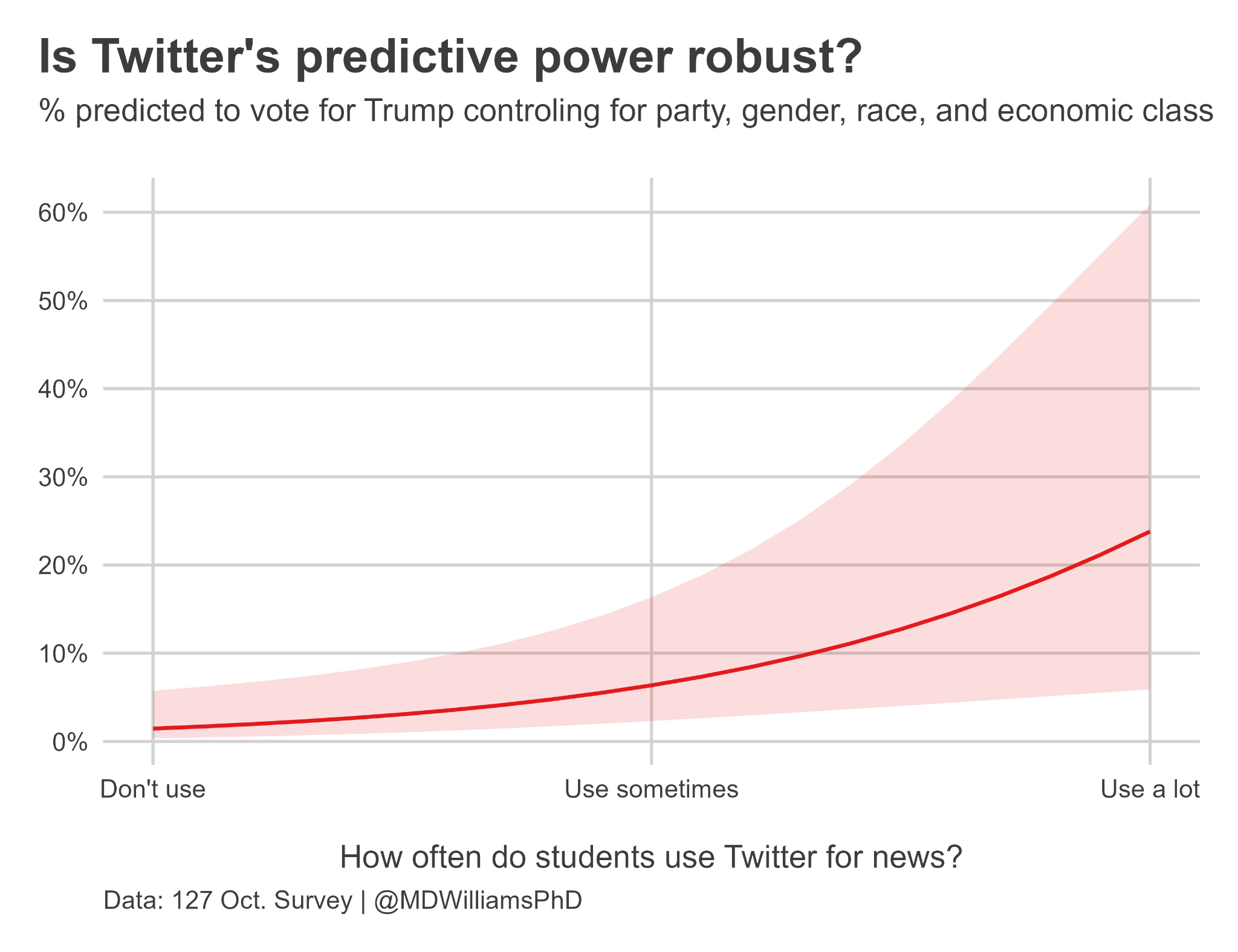

So far it looks pretty good for the bad-information-did-it argument, but before we get ahead of ourselves it’s worth noting that Trump voters might use Twitter for news because it’s a source of information that is a lot friendlier toward Trump compared to other platforms. We social scientists call this “endogeneity bias.” That’s a fancy way of saying that we have a chicken-or-the-egg problem. Which came first? Support for Trump, or using Twitter for news? It’s hard to answer this question, even with the best data in the world, but as a second best solution I decided to use a regression model to control for some variables that might explain away the relationship between Twitter usage and voting for Trump. Specifically, I controlled for party lean, gender, race, and a student’s economic background. The below figure shows the adjusted relationship between using Twitter for news and the likelihood that a student said they would vote for Trump. Even controlling for other factors, Twitter usage is still a good predictor of whether a student said they would vote for Trump. The relationship is more uncertain compared to looking at the raw data, but it’s statistically significant and still relatively substantial.

I can’t use this data to prove that Twitter caused students to vote a certain way, but the data is consistent with that argument. Students who used Twitter more for news were more likely to say they’d vote for Trump, and no other news source has the same level of explanatory power. This just goes to show that information matters in elections.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that it was just bad information. Lots of factors played a role in how the 2024 election played out. But there’s little doubt in my mind that exposure to bad information is part of the story.

Miles D. Williams (“DrDr”) is an avid gym rat and wannabe metal guitarist who teaches courses for Data for Political Research. He used to talk about his research on Twitter (it’s not “X”), but has switched to using Bluesky.